|

Saturday 21st of June saw the much-anticipated opening of our Heritage Centre. Guests from near and far afield attended the ceremony. They were serenaded by Matt Seattle on border pipes and chatted over tea and cakes in the Youth Hall. Speeches were given by David Hutchinson (History Society chairman) and Jan Rae (wife of Bill Rae, founder of our archive). After the ribbon was cut our visitors could see for themselves the results of all our hard work and were able to get a rare view of the bronze-age Thirlstane spearhead (part of the hoard found in the 19th century, including the famous 'Yetholm Shields'), which was loaned to us for the day by the SBC museum service. A minibus shuttled visitors to the kirk to see the companion display which has been created in the 'Upper Room' there. A selection of photos of the event can be seen below.

Since opening the new Heritage Centre has received a steady stream of visitors, who have left many enthusiastic comments.

0 Comments

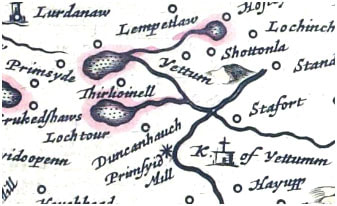

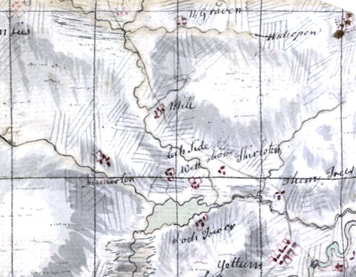

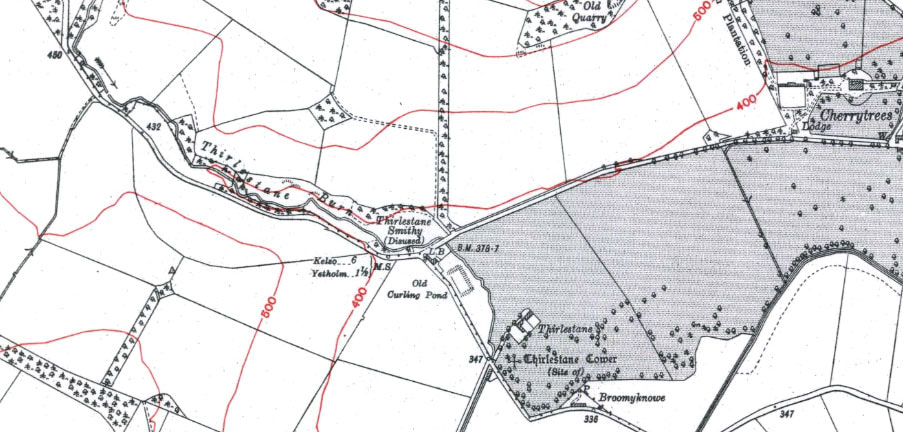

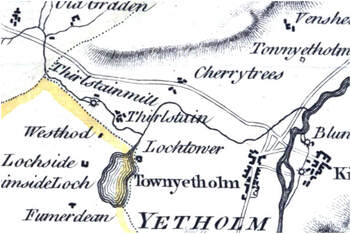

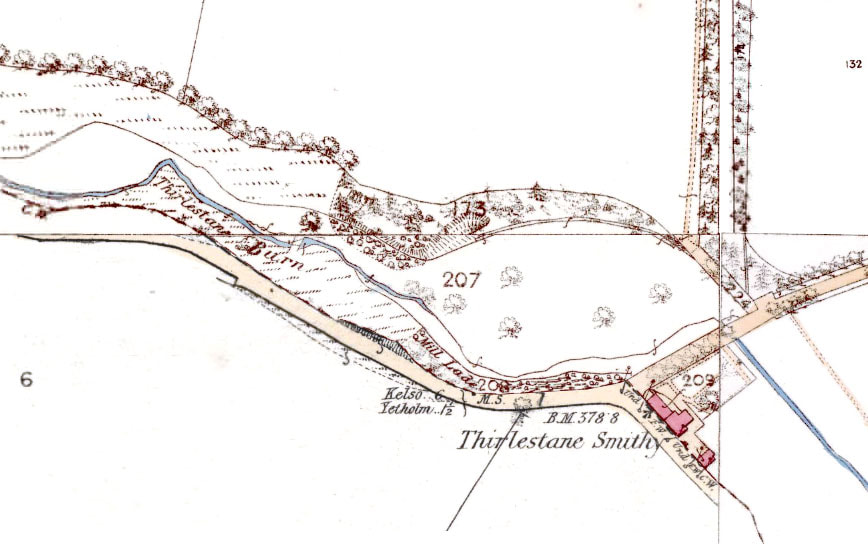

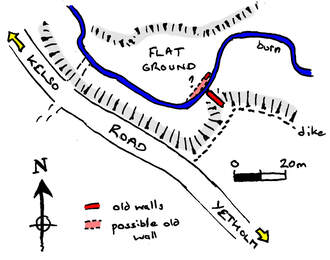

Just north of Yetholm, on your right as you drive toward Kelso, and halfway along a broad, nameless glen, lies Thirlestane House, now a private dwelling with an extensive garden. This is the remnant of a once much larger estate, now part of Cherrytrees, which included Thirlestane Hill to the north.  ‘Thirlestown’ is first mentioned in 1542 as part of a punitive raid by the English against settlements just northwest of Yetholm. Subsequently, it appears as ‘Thirlstane’ or ‘Thirlestonne’ in deeds and tax rolls from the seventeenth century*. The name is not uncommon and could have a number of origins – As Middle Scottish ‘Thirlistoun’ it may be a reference to a settlement occupied by peasants in obligation to a lord. As ‘Thirlestane’ it could be taken from the Berwickshire family name, itself derived from the word for a pierced stone (AS ‘thyrel stan’). However, similar names, such as ‘Thurlaston’ in England, suggest that such place names can be derived from the early settlement ‘tuns’ of individuals (e.g. Torlave, Turchile, Thorlak) which have been rationalised to something understandable by later inhabitants of the area. According to legend Thirlestane still had a surviving tower in the seventeenth century. By the nineteenth century, although the tower had gone Thirlestane had an associated smithy (now ‘Catch-A-Penny’), as shown on the first Ordnance Survey map of the area. But Thirlestane also had a mill. Thirlestane Mill may first show up on Blaeu’s 1654 map of the area as ‘Thirlioinell’. The name appears quite corrupt, and in all likelihood should say ‘Thirlis mill’, but the corruption is unsurprising. The information for Blaeu’s map was gathered by Timothy Pont around 1600 and only 50 years later, long after Pont’s death, was a map based on this information published in Amsterdam. Many of the names on Blaeu’s map are slightly distorted (e.g. Scarutch), presumably due to the original handwriting being difficult for the Dutch mapmakers to read.  However, even if this interpretation is wrong a mill belonging to Thirlestane certainly appears on a 1661 sale deed. A hundred years later a mill, probably the same, is shown on Roy’s Military map a little way up the Thirlestane Burn just below a side stream and just to the southwest of the old main road to Kelso as it skirts the south side of Thirlestane Hill. By 1770 ‘Thirlstainmill’, apparently a now little further downstream and with a mill lade (the artificial channel for running water to the mill wheel), appears on Stobie’s map of Roxburghshire. The mill is still mentioned as a nominal part of the Thirlestane Estate in the 1800 will of George Walker. However, by the time that Ainslie’s revised copy of Stobie’s map appeared in 1821 the mill was no longer marked. The mill is absent from all subsequent surveys, although there may be a trace of its existence in the Ordnance Survey 1 to 25 inch scale survey map of 1860. Here, a mill lade is shown just to the north of the new Kelso road west of Thirlestane Smithy. Having visited the site of the ‘mill lade’ there is indeed evidence for an artificial channel, not quite where marked on the map but to the NW and exactly paralleling the road. The channel sits several metres above the present course of the burn. That this channel must have once held water is clear from a series of breaches in it which have eroded gulleys down to the stream. At this point I want to digress and explain why anyone should put a mill on Thirlstane Burn. This tiny stream descends through a small gorge, or ‘cleugh’, cut by the stream in its drop from the open country of Greenlees and Graden farms in the northwest down to the glen in which Thirlestane House, Lochtower and Cherrytrees sit. The stream has a relatively steep gradient within the gorge, meaning that a there is a suitable head of water to run a mill just here. Incidentally, the word cleugh may have given the mill its other name, that of Clock Mill, which survived into the 19th century in the alternative name for Thirlestane Smithy, ‘Clock Mill Smithy’. By the way, in case you’re confused by the position of the road in the maps above, suffice to say that the Old Kelso-Yetholm Road used to run from Graden north of the cleugh and down past Cherrytrees. When the new Kelso-Yetholm Road was built at some time between 1820 and 1840 the road was diverted south of the cleugh, before splitting, one part rejoining the Cherrytrees road, the other continuing in a more straight line to Yetholm. To return ... so where was the mill? As a little experiment, I’ve superimposed both the Roy and Stobie Maps over a 1918 OS map of the area. The Stobie map is cartographically quite accurate and allows for a reasonably simple overlay, placing the mill clearly just to the west of Thirlestane Smithy and just north of the burn. This also places the mill lade in about the right position to match the remains of the channel. So it looks like we have a rough idea of where the mill was. Unfortunately Roy’s map is not so cartographically accurate and needed some distortion to overlay onto the OS map in order that Graden (not shown), Thirlestane and the stream were in the right places. Regardless, it shows the mill considerably higher up Thirlestane Burn. This would be relatively easy to write-off due to the inaccuracy of the map, but the position of an incoming stream just by the mill matches the position of an old stream which is now dry. A few weeks ago I chanced to look at the stream just near the point where Roy’s mill would be. I found this: It’s a section of lime-mortared wall about 4 metres long and 1.5 metres high, made up of large, rounded river cobbles. The wall has been slightly truncated at the river’s edge, but it appears that the river has not shifted much, as a small section of mortared wall, approximately at right angles to the first, can be traced on the other side of the stream below a fallen tree. Both walls have been built upon an outcrop of rock in the river such that the water makes a small waterfall here. The ground on the upstream side of the wall is soft and waterlogged. The style of the wall tells us two things; firstly that the wall is for a building or dam. Normal enclosure dikes for stock were dry-built, i.e. without the use of mortar. Secondly the wall is old. The use of river cobbles seems to have been largely abandoned in the late eighteenth or nineteenth century when enclosure required the opening up of many quarries to supply the new need for more stone.

Given the unusual location of this wall, it looks like the wall might be part of a milldam. Such dams were used to store water in small streams with low flow power to use for occasional milling operations. If it is a milldam then either there were two mills, which is possible if they are not the same age. However, the mill lade and milldam may be part of one mill system. The milldam base sits at an elevation of about 129 metres above sea level. The mill lade channel has an elevation of between 120 and 119 metres, which, given it has probably silted up, means that it could be up to a metre deeper than this. The distance between the two is about 500 metres, giving a channel gradient of 1 in 50, so it’s perfectly possible that the dam supplied the lade and the mill. We have evidence of a milldam and a mill lade, so it might seem surprising that the mill buildings should have disappeared so completely. However, the combined effects of stone robbing to build enclosure walls, road engineering works and the rapid downcutting of the stream in the last two-hundred years have made the location of the mill far less obvious than it might otherwise have been. Wherever Thirlestane mill was, it was probably abandoned at the beginning of the 19th century after the new, improving landowner, Mr Adam Boyd of Cherrytrees, bought Thirlestane from the Walker family. Many such local mills were abandoned in the coming century due to ‘outsourcing’ and competition from coal in a new age of cheaper energy. It makes one wonder if such mills might yet be back. References: The information on Thirlestane’s early history comes from J. Bain’s 1890 edition of the Hamilton Papers Vol 1 p304 (https://archive.org/details/cu31924091786032 ) and from J.H. Stevenson’s edition of the Registrum Magni Sigilli Regum Scottorum (Register of the Great Seal) Vol 11, p54, (https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101073592006&view=1up&seq=1). The Blaeu, Roy, Stobie, Ainslie and Ordnance Survey Maps of Roxburghshire come from the National Library of Scotland map archives (at https://maps.nls.uk). The 1678 Tax Roll information on Yetholm Parish and the Ordnance Survey Name Book information on Thirlestane Tower (Roxburgh Vol 42) can be found at scotlandsplaces.gov.uk The record of Clock Mill Smithy can be found in the 1851 & 1861 Census Returns (ref 811/2/18 & 13 at https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/guides/census-returns. The records of the Walker family (of Thirlestane) are in the Scottish Borders Archive SBA/183 box 2/1 (49). N Pegler |

Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed